By Dylan Duncan

A malware phishing campaign that began spreading DarkGate malware in September of this year has evolved to become one of the most advanced phishing campaigns active in the threat landscape. Since then, the campaign has changed to use evasive tactics and anti-analysis techniques to continue distributing DarkGate, and more recently, PikaBot. The campaign surged just one month after the last seen QakBot activity, and follows the same trends used by the infamous threat actors that deploy the QakBot malware and botnet. This campaign disseminates a high volume of emails to a wide range of industries, and due to the loader capabilities of the malware delivered, targets can be at risk of more sophisticated threats like reconnaissance malware and ransomware.

In August of this year, the FBI and the Justice Department announced that they had disabled the QakBot infrastructure. Since then, QakBot has remained silent, with no significant activity seen from the malware infrastructure. While direct attribution between the QakBot threat actors and this campaign can be difficult, we can show the similarities between the two. Starting with the timeline of the campaign, Cofense Intelligence last reported on QakBot towards the end of June whereas DarkGate reports first emerged during July. The new campaign that is delivering DarkGate and PikaBot follows the same tactics that have been used in QakBot phishing campaigns. These include hijacked email threads as the initial infection, URLs with unique patterns that limit user access, and an infection chain nearly identical to what we have seen with QakBot delivery. The malware families used also follow suit to what we would expect QakBot affiliates to use. Along with many other capabilities, both malware families can act as loaders with the ability to add additional malicious payloads to unknown infected machines.

Figure 1: Timeline of QakBot and DarkGate/PikaBot Campaign based on Cofense Intelligence Sightings.

Inside Look at the Phishing Campaign

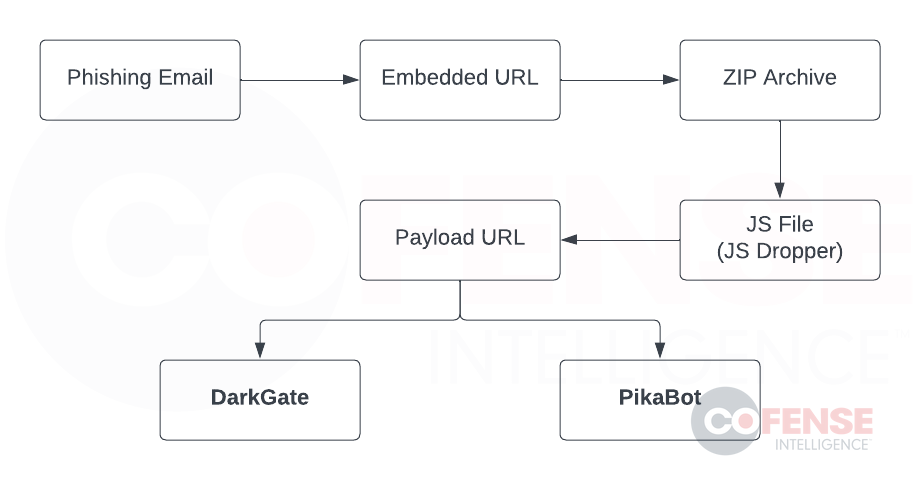

This campaign is undoubtedly a high-level threat due to the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that enable the phishing emails to reach intended targets as well as the advanced capabilities of the malware being delivered. During the lifespan of the campaign, we have noticed several different infection chains, almost as if the threat actors were testing different malware delivery options. However, a favored infection chain to deliver the malware has been made apparent and is illustrated in Figure 2. This infection chain follows in line with that seen in QakBot campaigns during May of this year (Active Threat Reports (ATRs): 325113, 324360, 323510).

The campaign begins with a hijacked email thread to bait users into interacting with a URL that has added layers that limit access to the malicious payload only to users that meet specific requirements set by the threat actors (location and internet browser). This URL downloads a ZIP archive that contains a JS file that is a JS Dropper, which is a JavaScript application used to reach out to another URL to download and run malware. At this stage, a user has been successfully infected with either the DarkGate or PikaBot malware.

Figure 2: Most common infection chain used in the campaign.

DarkGate and PikaBot are both considered advanced malware with loader capabilities and anti-analysis behavior. This is attributed to the advanced features that each family offers and the steps within each malware config that make analysis more complex for malware researchers. Most notable, and what would be the most appealing to threat actors like the QakBot affiliates, is that both malware families can deliver additional payloads once successfully planted on a user’s machine. A successful DarkGate or PikaBot infection could lead to the delivery of advanced crypto mining software, reconnaissance tools, ransomware, or any other malicious file the threat actors wish to install on a victim’s machine. More details on the individual families can be found below:

- DarkGate was first seen in 2018 and is capable of cryptocurrency mining, credential theft, ransomware, and remote access. The capabilities outlined do not come default installed but must instead be executed similarly to plugins. It has multiple methods of avoiding detection and two distinct methods of escalating privileges. DarkGate makes use of legitimate AutoIT files and typically runs multiple AutoIT scripts.

- PikaBot is a new malware family first seen in 2023. It is classified as a loader due to its ability to deliver additional malware payloads. It contains several evasive techniques to avoid sandboxes, virtual machines, and other debugging techniques. It has been observed to exclude infecting machines in CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) countries. These countries were all members of the former Soviet Union.

Evasive Phishing Tactics Combined with Anti-analysis Techniques

This campaign combines well-known evasive phishing tactics with techniques known to disrupt malware analysis processes. The first steps of this campaign are far more complicated than the average phishing attack. The threat actors disseminate the phishing emails through hijacked email threads that may be obtained from Microsoft ProxyLogon attacks (CVE-2021-26855). This is a vulnerability on the Microsoft Exchange Server that allows threat actors to bypass authentication and impersonate admins.

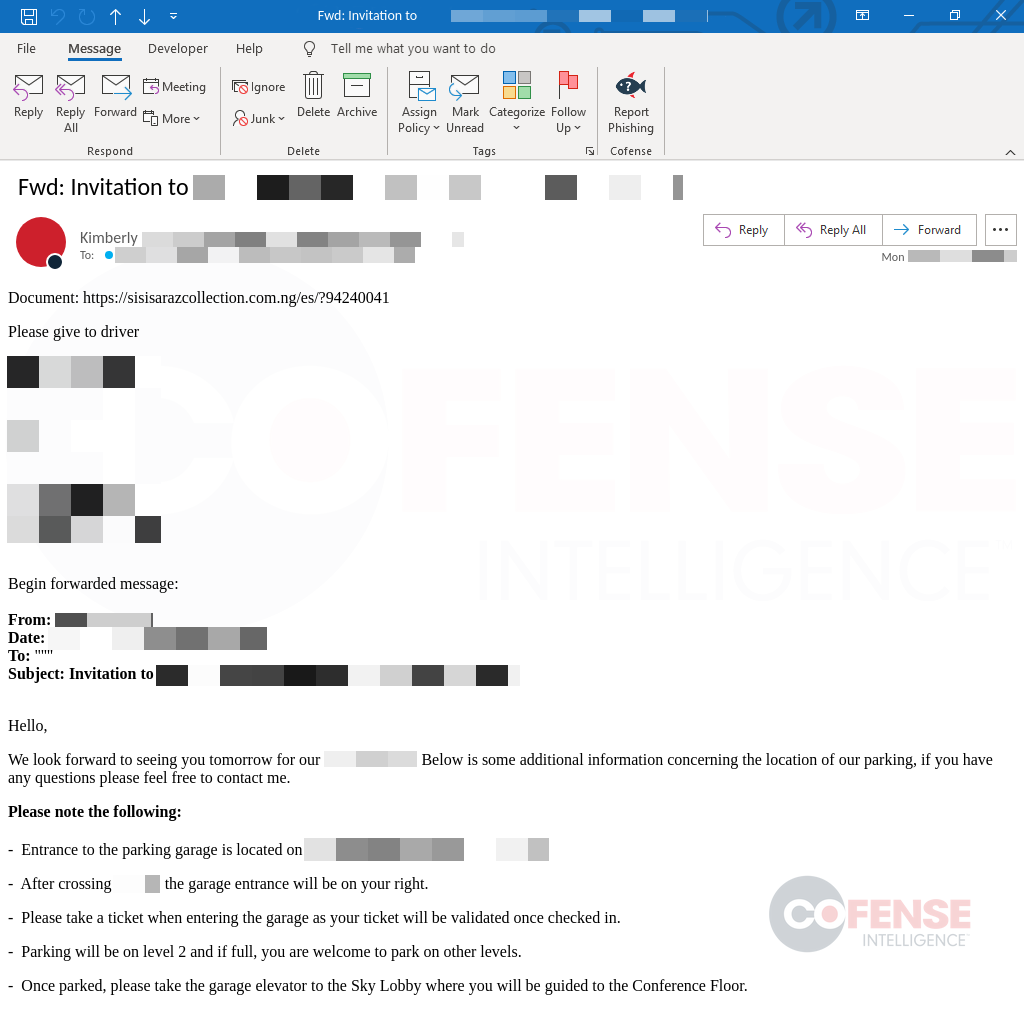

Responding to email threads creates an added layer of trust between the threat actors and the target, since the target may recognize the conversation and believe the sender to be trusted. Figure 3 (ATR 351964) below is a real phishing example that reached an enterprise user’s inbox. The threat actors provided a message relevant to the hijacked thread to the target with the inclusion of a malicious link. This is one of the many factors that give campaigns that utilize this tactic a higher chance of success.

Figure 3: Real hijacked email thread example that delivered PikaBot (ATR 351964).

In the email, you can see the malicious URL shown in Figure 4. This URL contains a unique pattern like that seen in QakBot phishing campaigns (ATR 325113). These URLs are more than your average phishing URL; threat actors have included added layers to limit access to the malicious file that it delivers. For example, to retrieve the download users must be using Google Chrome browser in a specific location set by the threat actors, specifically in the United States.

Figure 4: Phishing URL used to download and run malicious JS Dropper.

Experimenting with Malware Delivery Options

The most common delivery mechanism seen in this campaign is JS Droppers, however, Cofense Intelligence has been tracking this campaign since the beginning and has documented each infection chain utilized in this campaign. The most notable, outside of the JS Droppers, include the use of Excel-DNA Loader, VBS Downloaders, and LNK Downloaders. Threat actors use these methods for downloading and installing their malware every day so it’s not uncommon to see a campaign this advanced incorporate these additional methods within the infection chains. The most unusual method would be the incorporation of the Excel-DNA Loaders. This is a relatively new delivery mechanism (first seen in 2021) that became very popular early on and incorporates the use of Microsoft Excel add-ins to download and run malicious payloads.

- JavaScript Dropper (JS Dropper) is a script application written using a Microsoft ECMAScript dialect known as Jscript, commonly referred to as JavaScript. These files can be identified by the file extension JS and can allow threat actors to create a malware delivery tool that is both natively executable on the Windows platform and highly malleable and adaptable. In most cases, these files are used to download, write to disk, and run a Windows PE executable or DLL payload.

- Excel-DNA Loader (Excel DotNET for Applications) is an open-source project that is used for creating XLL files as add-ins for Microsoft Excel. An XLL file is a Microsoft Excel add-in that can have many legitimate workplace uses, but threat actors have taken these add-ins and configured their files to reach out to payload locations to download and run malicious payloads. This method of delivering malware was first observed in 2021 delivering a wide range of malware, most notable was the Dridex banking trojan.

- VBS Downloaders leverage Visual Basic runtime applications, usually available within Windows environments, to carry out the download and execution of malware binaries. These scripts use the file extension VBS and run through Microsoft Office products or invoke Windows executable applications, like cscript.exe or wscript.exe, from the command line.

- LNK Downloader is a Microsoft LNK shortcut downloader that abuses the trusted nature of being a “safe” file format to secure entry to a victim’s computer before downloading and executing a malware payload. These files, known by the LNK extension, play the role of a file shortcut in Windows Explorer. However, threat actors have repurposed them to make a reference to their own content in such a way that allows executable script elements to run within the Windows environment.

This campaign is advanced, well-crafted, and has already evolved since it was first seen in the wild. The threat actors behind the campaign maintain skills beyond the average phisher, and employees should be aware that this type of threat exists. Cofense Intelligence will continue to monitor the changes and the strong similarities to QakBot that this campaign exhibits.