By: Kahng An, Intelligence Team

Modern Windows systems include many built-in features that help applications run smoothly and support everyday user activity. Unfortunately, many of these built-in functionalities can be exploited by threat actors in order to have malware payloads remain on a system and run without user interaction. These different features can be abused to be what security researchers call “persistence mechanisms.”

Persistent malware is typically intended to run on system startup, providing threat actors with a way to maintain a compromised system that lasts beyond when the computer is shut down. With this foothold, they can monitor an infected system, change tactics, or deploy additional payloads at any time.

Understanding how malware can remain persistent and undetected on a machine is key for identifying compromised hosts and preventing long-term attacker access.

This report will cover some common persistence mechanisms for malware on Windows systems and relevant examples of various malware families that take advantage of these persistence mechanisms.

Key Takeaways

- Threat actors can abuse multiple legitimate and necessary system administration components of Windows, such as registry keys and scheduled tasks, to make malware persistent between login sessions.

- Persistence mechanisms will still leave indicators of compromise (IOCs), though they require security teams to be aware of different ways automatically executing programs can be hidden in legitimate Windows system behavior.

- Threat hunting for common persistence mechanisms on a proactive and reactive basis can help prevent and contain malware threats.

- Some persistence mechanisms, such as script payloads found within registry keys, can be used to run malware without using files that are dropped or downloaded to the file system.

What is Persistence for Malware?

In general, persistence is how threat actors establish footholds on an infected system after achieving initial access. For example, remote access trojans (RATs) can be used to remotely access an infected host any number of times after initial infection, often giving threat actors a way to monitor infected systems and deliver additional malicious payloads.

However, to remain as a persistent threat on the infected system, the RAT would need to be run whenever the infected user is logged in. A persistence mechanism is the way in which malware can be run automatically when the infected system is active. Persistence mechanisms typically abuse legitimate operating system functionality to automatically run programs or execute commands upon startup.

Common Windows Persistence Mechanisms

Windows offers multiple ways to automatically run programs upon user login or other specific events. These systems are critical to how the operating system functions but can also be abused to run malware without the user’s knowledge.

Windows Registry Keys

Windows stores various configuration settings for the operating system in a database called the Windows Registry. This database is critical to how Windows functions, and it notably has a number of different registry keys that will execute programs when the user logs in.

These registry keys can be maliciously abused by threat actors to run persistent malware either as an executable or a script payload run via the Windows Command Prompt, PowerShell, Windows Script Host (wscript.exe or cscript.exe), or other similar programs.

While explaining how the Windows Registry functions in depth is out of scope for this report, it is important to note that the Windows Registry is separated into multiple registry hives (effectively a folder within the database). The HKEY_CURRENT_USER hive (often shortened to HKCU) contains configurations for the currently logged in user.

The HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE hive (often shortened to HKLM) contains configurations for all users on the machine. While Windows has a built-in utility for managing the registry through Registry Editor (commonly known as Regedit), there are also more advanced registry forensic tools, such as Registry Explorer, that can be used to manage and view registry hives.

Some of the most common registry keys for malware persistence are the Run keys. The Run keys are a collection of multiple different registry keys that all run programs or execute commands when the user logs in.

While the Run keys can exist in multiple different registry hives, they are separated into keys that will run on every login event (Run) and keys that will only run one time (RunOnce). The following is a list of all the Run keys available on modern versions of Windows:

Table 1: Run keys

Registry Key | Description |

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | Runs a specified program or command when the currently logged in user logs in. |

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce | Runs a specified program or command one time when the currently logged in user logs in. |

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | Runs a specified program or command when any user account logs in. |

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce | Runs a specified program or command one time when an administrator account logs in. |

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnceEx | Runs a specified program or command one time when an administrator account logs in. This key is a special exception that is not created by default since Windows Vista but can still be created manually. |

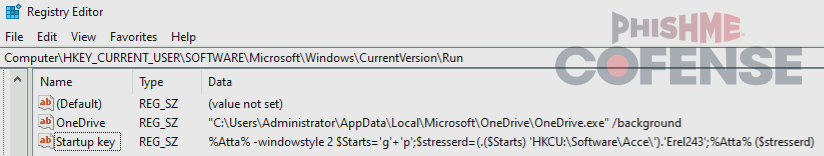

A notable quirk about how the Run keys function is that a key can specify a program to run with additional arguments, usually in the form of additional flags/parameters. Threat actors can abuse this to do things like run staged payloads that are found on the file system or embedded script payloads that are stored in the registry as a fileless payload. For example, Figure 1 shows a Run key called “Startup key” that contains an embedded PowerShell script that runs the obfuscated script contents of another registry key (HKCU\Software\Acce\Erel243) shown in Figure 2.

.png)

Figure 1: ATR 400745 features a Run key that runs a payload in HKCU\Software\Acce\Erel243.

.png)

Figure 2: The script payload staged in HKCU\Software\Acce\Erel243 as a form of fileless persistence.

Another important quirk is that RunOnce keys will by default delete themselves before running the specified command. Because the registry key will not exist in the registry hive after execution, analysts would need to rely on Windows log events, existing registry/system backups, or more complex host forensic techniques to analyze infected hosts.

Threat actors can abuse this functionality by creating new RunOnce keys shortly before user logout or system shutdown to create persistence that does not leave a registry key that can be easily found by the user during active sessions.

Like the Run keys, the Winlogon key executes programs or commands when the user logs in. Its intended use is for handling actions when the user first logs in and when Ctrl-Alt-Delete is pressed. Similar to the Run keys, Winlogon keys can be found in the HKCU hive (HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\) or HKLM hive (HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\) which govern user-specific and system-wide Winlogon behavior respectively.

While there are multiple ways that Winlogon can be abused, the following lists some of the frequently abused keys within the two hives:

Table 1: Winlogon keys

Registry Key | Description |

Winlogon\Notify | Can be used to run arbitrary DLLs when triggered by a Winlogon event. |

Winlogon\Userinit | Runs a specified program (userinit.exe by default) when the user logs in. |

Winlogon\Shell | Runs a specified program (explorer.exe by default) when the user logs in. |

While less common than Run keys, Winlogon keys can provide another way for threat actors to persist malware on startup. For example, consider an embedded malicious PowerShell script that is run after “explorer.exe” and “userinit.exe” in the Shell and Userinit subkeys respectively. Because these registry key edits do not interfere with expected legitimate Windows system behavior, users and administrators may not even be aware that malware is running on the system.

While there are many more examples of registry keys that can be abused for malware, the Run keys and Winlogon keys are some of the most prevalent. This is likely because they are simple mechanisms that will always run on startup/login, allowing for reliable execution of a malicious payload before the user interacts with the system for long.

Additionally, Run keys are often used by legitimate programs that can also be repurposed as malware such as ConnectWise ScreenConnect (tracked by Cofense as ConnectWise RAT).

Windows Shell Startup Files

Windows offers a way to run programs on user login without interacting with the Windows Registry via special startup folders that contain programs to run upon user login. There are two startup folders, one for the currently logged in user (%APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup) and one for all users on the system (C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup).

The two folders can also be conveniently accessed via the “shell:startup” and “shell:common startup” commands in the Run command window or address bar of File Explorer. Shell startup files and Run keys are the two most common forms of persistence found in ATRs.

This form of persistence is commonly done by staging the malware executable or a script that runs the malware within the startup folder. For example, a malicious binary can be added to the startup folder to run a malicious payload.

Alternatively, a malicious script (such as a batch script) can be added to the startup folder to run malicious payloads contained within the script contents. Other file types that can be executed, such as LNK files, can also be used within startup folders for persistence.

Windows Scheduled Tasks

The Windows Task Scheduler is a system utility used to automatically run programs or scripts based on specific time-based or event-based triggers. Scheduled tasks can also be abused by threat actors to run malware on system startup or on a particular scheduled event such as a certain time of day or when a specified program is launched.

Threat actors may find scheduled tasks more useful than the previous persistence mechanisms because they allow them to run payloads outside of system startup and/or user login.

Scheduled tasks can be viewed and managed via the Task Scheduler, a built-in GUI application intended for administrators. For those who prefer command line utilities or automation scripts, scheduled tasks can also be managed through the schtasks command or via PowerShell ScheduledTasks cmdlets.

While this may be convenient for users, security teams are likely more interested in quickly reviewing scheduled tasks in bulk. Thankfully, scheduled tasks create Windows Registry keys under two different keys (HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Schedule\TaskCache\Tasks and HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Schedule\TaskCache\Tree) that can be parsed out with various Windows Registry forensic tools. Additionally, each scheduled task in versions of Windows since Windows Vista creates an associated XML document in C:\Windows\System32\Tasks that describes valuable information such as when the task was created, if it is enabled, when it runs, and what happens when it runs.

Windows Services

Windows services are programs that run in the background and are often automatically run on system startup. By default, Windows needs many services to handle operating system functionality such as managing network connections, file indexing, and hardware management. Additionally, legitimate programs may create services for running database servers, background utilities, and monitoring.

All these qualities make Windows services interesting for threat actors wanting to make sneaky, persistent malware.

Services can be viewed within Task Manager, though the Services Manager (“services.msc”) provides far more detailed information that can be useful when managing and defining services. Notably, each service creates a subkey within the HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services key, allowing security teams to review defined services in aggregate after parsing out all the keys via a Windows registry forensics tool. Each key includes the name of the service, the application it runs, and under what conditions the service is automatically run.

While Windows services can be a stealthy way to add persistence, in practice they are generally uncommon in malware ATRs. This is likely because Windows services are a system component intended for system administration and accordingly require administrator privileges to manage services. All three of the previously mentioned persistence mechanisms are much more common than Windows services and do not require administrator privileges to use.

Conclusions

While there are many more persistence mechanisms that threat actors can use for malware, this report covers the most common and basic ones that are often found in malware ATRs. Regardless of the specific techniques used, malware persistence relies upon abusing legitimate system functionality to run without the user’s knowledge.

Some additional mechanisms that may be of note include editing existing shortcut files to launch malicious payloads and Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) event handlers.

More advanced techniques that are far outside the scope of this report include malicious driver files (installing malicious drivers that act as persistent malware), DLL sideloading (replacing legitimate program DLL files with malicious ones that are executed when the associated application is run), and Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) bootkits (malware that infects computer firmware that is run before the operating system is started).

Additionally, non-Windows operating systems have similarly abused system functionality such as startup items in MacOS and the various startup script options available on Linux distros such as systemd unit files, OpenRC init scripts, and cron jobs.

Mitigations

Threat hunting for persistent malware can be complex depending on how evasive the techniques used are and how much visibility an organization has on their systems. While most malware samples use simple, well documented persistence mechanisms noted in this report, particularly advanced threat actors may deploy more complex persistence (such as kernel or bootloader level persistence) or employ anti-forensic techniques (such as avoiding shared indicators between infected hosts and disabling logging) to confuse security teams.

Additionally, having minimal to no system logging and monitoring can make detecting and responding to threats difficult if not practically impossible. For both reasons, Cofense Intelligence recommends the following for basic proactive and reactive persistence threat hunting:

- Use endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools to proactively monitor systems and reactively respond to threats.

- Maintain awareness over what programs/processes legitimately need to be run automatically and what programs/processes might be anomalous.

- Consider scanning systems with Autoruns, a part of the Sysinternals Suite, that provides a list of programs that run on system startup, login, and execution of various built-in Windows applications.

Persistent malware remains a serious risk, but the right intelligence and detection tools can help teams identify and remove these threats quickly. At Cofense, we are committed to helping organizations defend against today’s most advanced phishing attacks with speed, accuracy, and efficiency. Schedule a demo today to learn more.