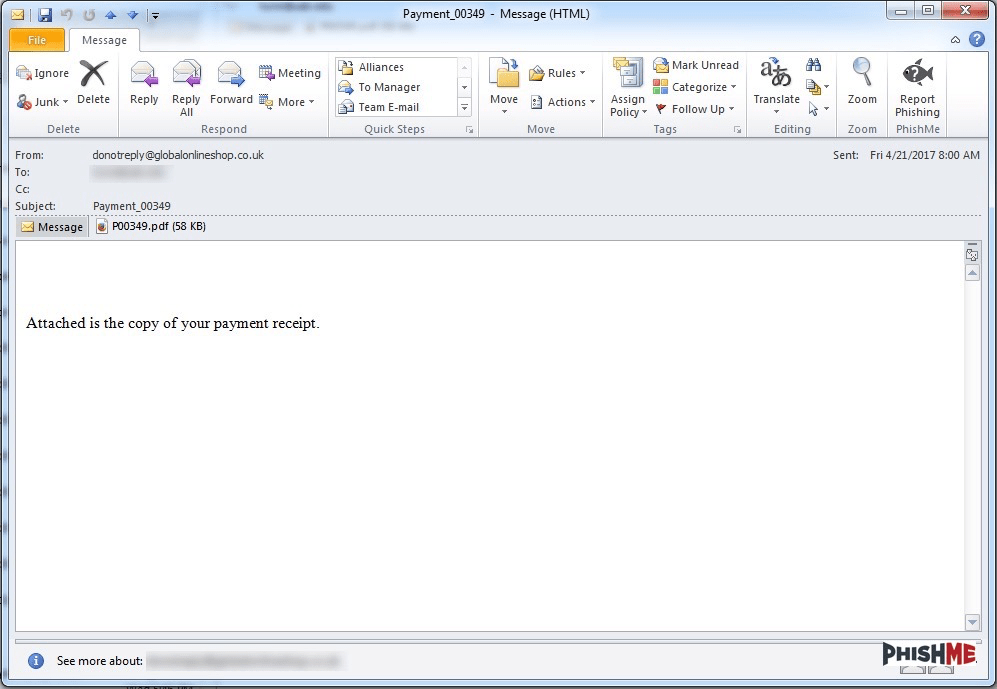

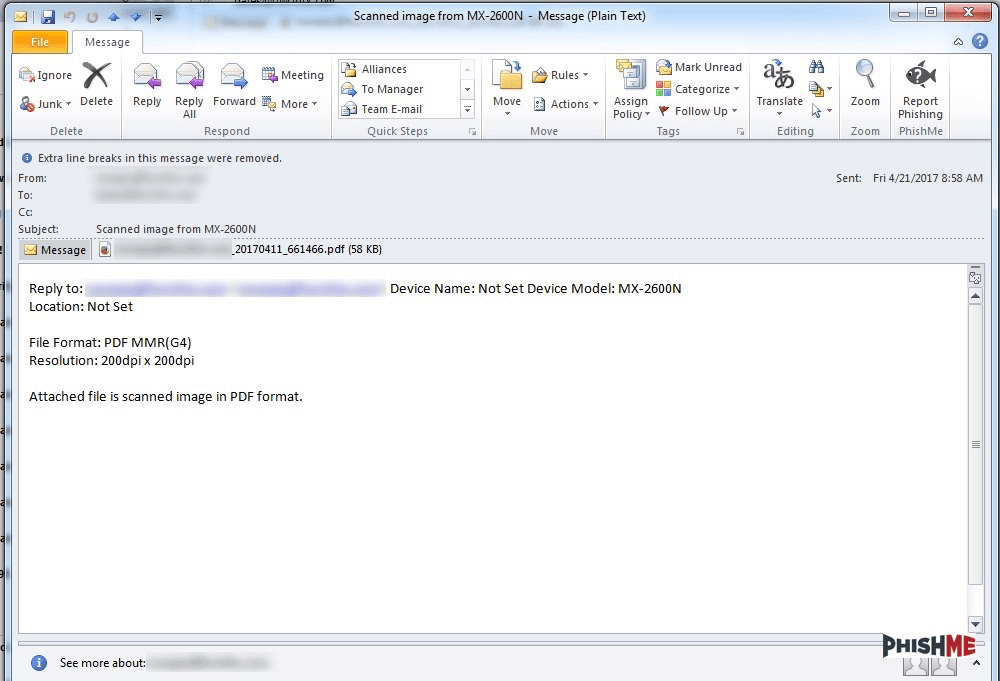

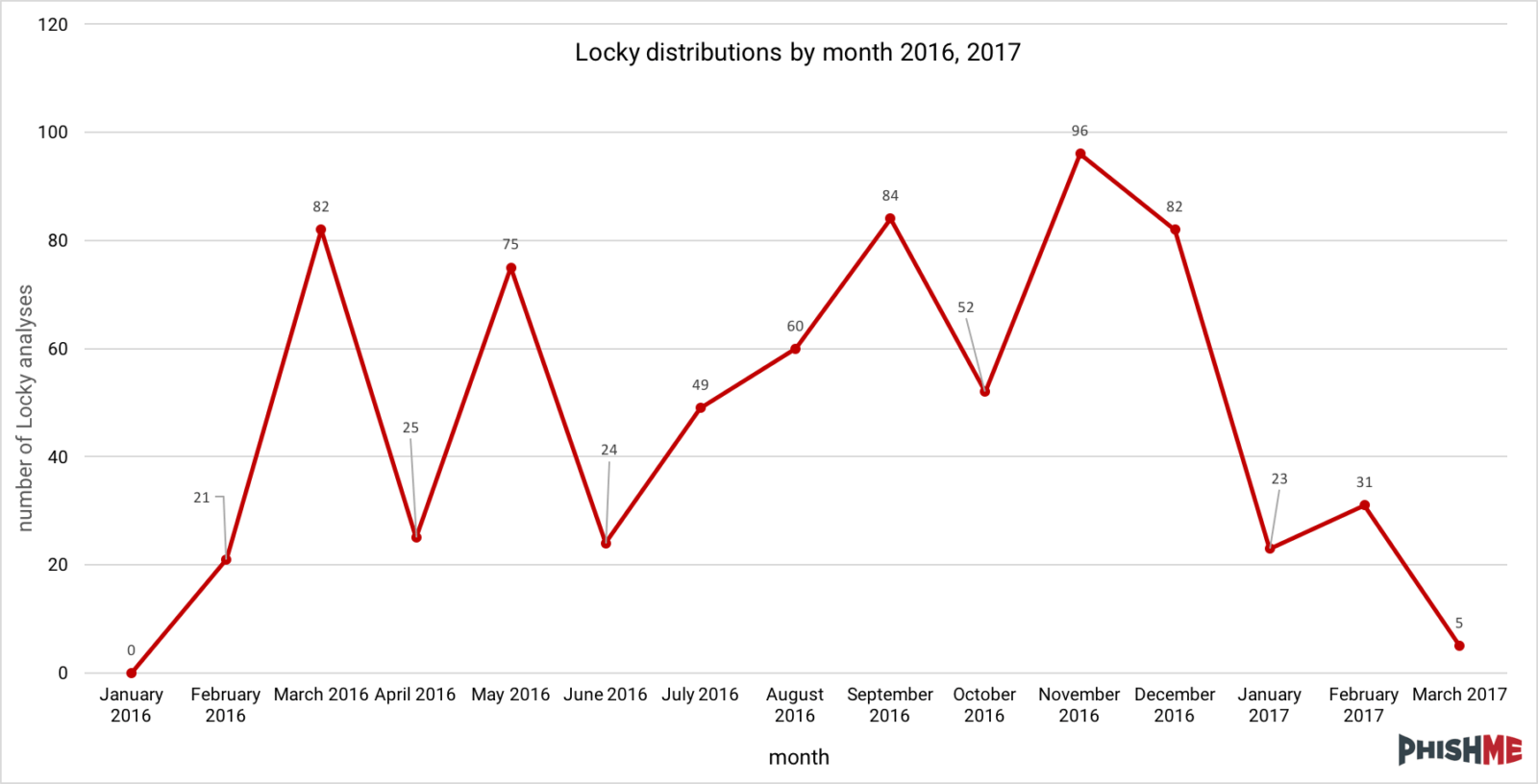

The ransomware that defined much of the phishing threat landscape in 2016 raged back into prominence on April 21, 2017 with multiple sets of phishing email messages. Harkening back to narratives used throughout 2016, these messages leveraged simple, easily-recognizable, but perennially-effective phishing lures to convince recipients to open the attached file.

However, the methods used to deliver the Locky payload are significantly different from those used for much of 2016. Instead, these newest Locky distributions leveraged a technique that has become popular in the distribution of the Dridex botnet malware, as documented in PhishMe’s April 18th post on that malware’s distribution methodology.

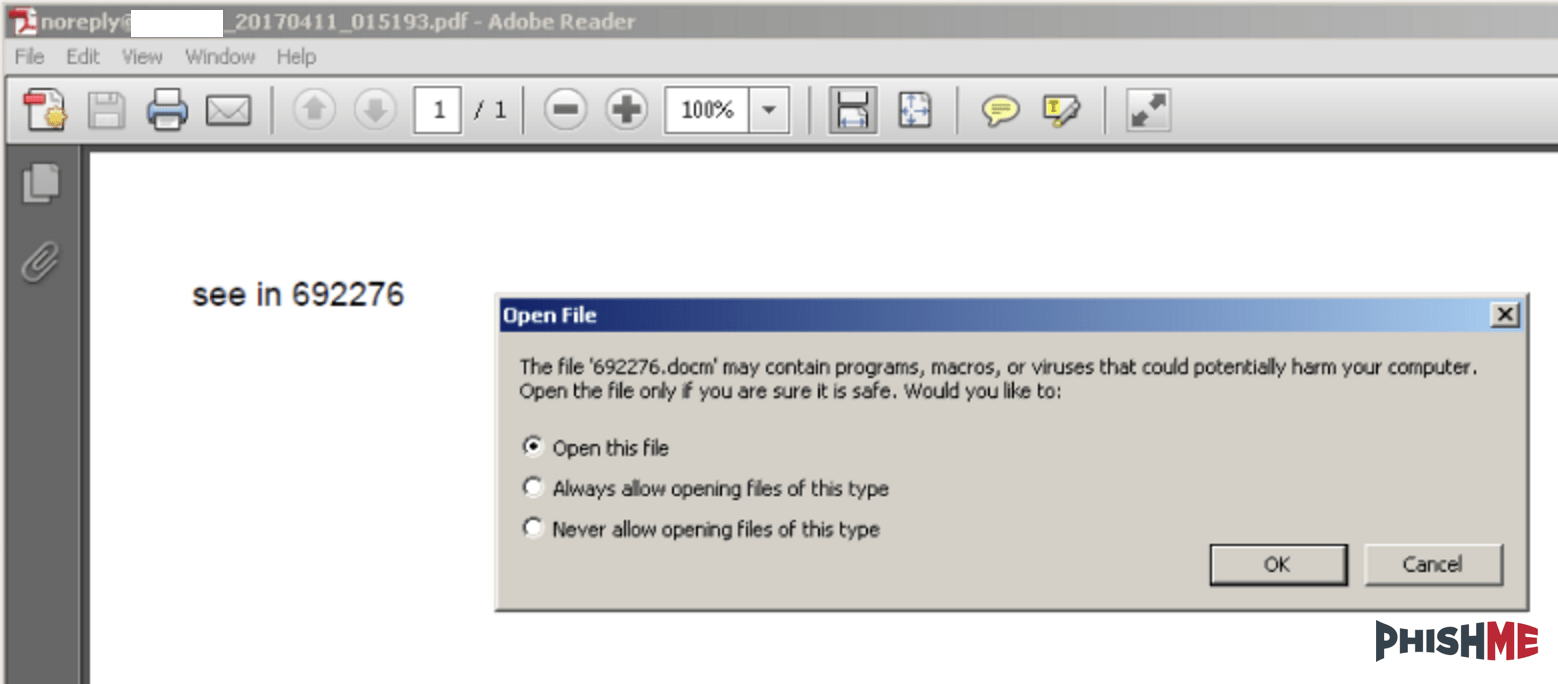

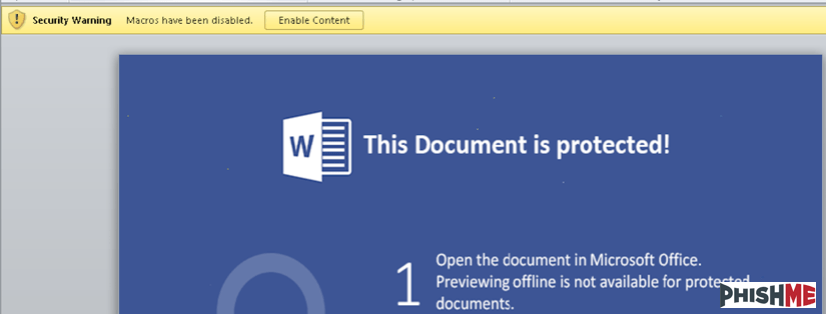

The technique in play with these phishing attacks attempts to take advantage of the awareness and education surrounding macro-based delivery as it has proliferated over the past few years. As more and more threat actors utilized this technique, it became clear to both defenders and potential victims what these attacks look like and how they work. This has created an increasingly less advantageous environment for threat actors using Office macro documents. The recent distribution of the Dridex malware using this technique in conjunction with a PDF document broke from the expectations set for potential victims about how this technique looks. The threat actors seek to defy the expectations created by the increased awareness about Office macro attacks by altering how they are presented to victims.

As PhishMe documented in earlier coverage of the Dridex malware, these PDF attachments use a relatively simple and straightforward infection process. Upon opening the PDF, the recipient is prompted to give permission for the PDF reader application to open a second file. This second file, extracted from within the PDF document, is a Word document with a macro script application used to download a Dridex payload. This adds another unexpected step to the infection process and thereby breaks from the common technique used to deliver macro documents. Figures 2 and 3 show the two-steps used by the threat actor to convince victims to engage with the macro document.

Following the 2016 holiday season, Locky distributions seemed to evaporate, leaving only a handful of small distributions throughout the first quarter of 2017. During that period, several other ransomware varieties appeared on the phishing landscape and the ever-present Cerber encryption ransomware maintained a significant share of the ransomware market. The lucrative business of ransomware is one that threat actors were unlikely to abandon. Furthermore, a robust tool like the Locky encryption ransomware likely provides a reliable means to turn profits in that market. The reinvigorated distribution of Locky serves to reinforce that while there was an extended hiatus, this ransomware is here to stay.

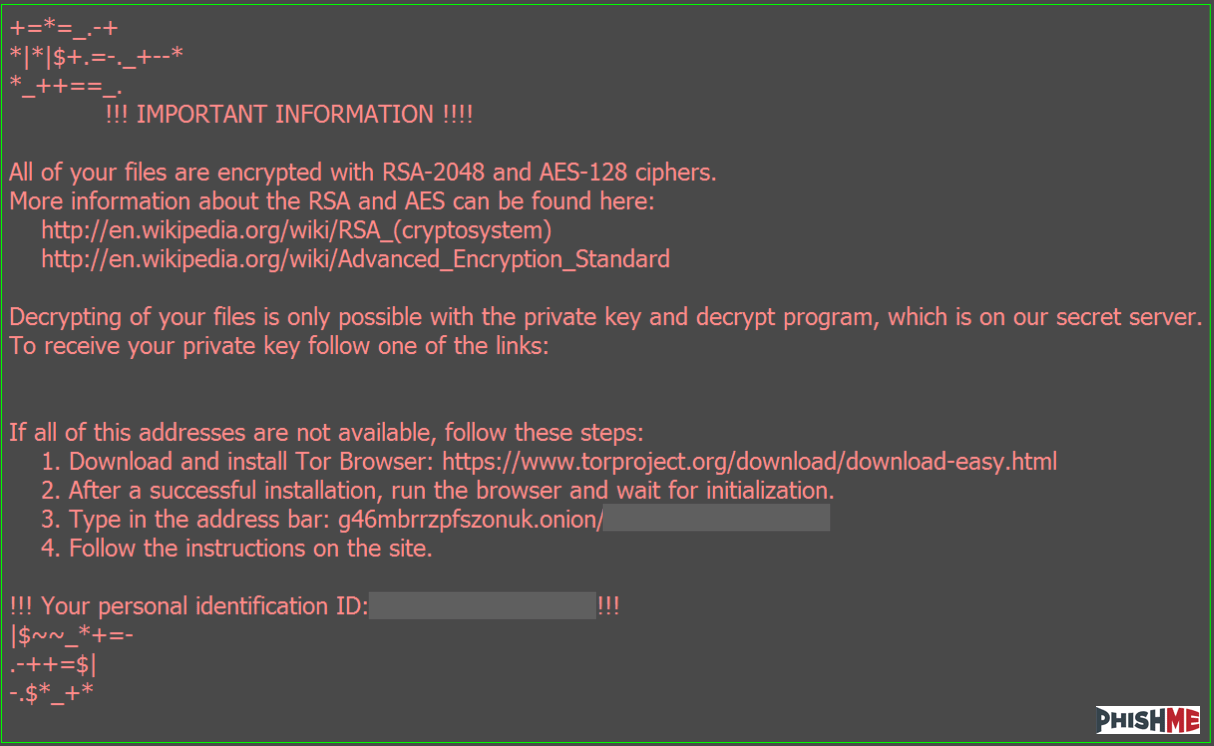

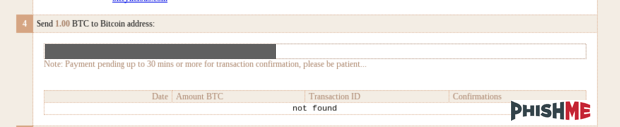

Locky itself seems to still carry out its same functionality with cruel efficiency, seeking out and encrypting a wide variety of valuable and mission-critical documents and files on victims’ machines. Its all-too-familiar ransom notes are still sport a red-on-black color scheme and direct victims to a bland, beige payment site. One notable fact is the request that victims install the Tor browser to view the ransom payment site. This is likely in response to the blocks frequently put into place by Tor proxy services such as Tor2Web.org and the burden of maintaining a dedicated Tor2Web proxy site.

These most recent Locky distributions present an ambitious ransom amount on the payment site—one Bitcoin. At the time of publication, the asking price for one Bitcoin was over 1200 USD and over 1100 Euro. This is a significant increase over many of the ransoms observed in 2016 that ranged from 300 USD to 500 USD in equivalent Bitcoin.

Despite the apparent ambition and aggression demonstrated by these reinvigorated Locky distributions, these threat actors have not yet found a guaranteed recipe for success. The best efforts of these attackers can still be foiled by a holistic phishing defense strategy. Robust user education and empowerment turns potential victims into assets who can identify and report attacks in near-real-time to those tasked with defending an enterprise. These defenders can then couple that internal intelligence collection with external threat intelligence to gain insight into the context for how and where phishing attacks are being carried out and the resources used to support them.

Indicators related to these newest Locky attacks.

URIs providing Locky executables:

hola://abcenglishclub[.]com/9yg65

hola://aielloengineering[.]com/9yg65

hola://aim-controls[.]com/9yg65

hola://bhmech[.]com/9yg65

hola://cindysplace[.]net/9yg65

hola://clayhero[.]com/9yg65

hola://dont[.]pl/9yg65

hola://ercelectronics[.]com/9yg65

hola://erius[.]nl/9yg65

hola://flexza[.]net/9yg65

hola://labprocomalumnos[.]site/9yg65

hola://rootcellar[.]us/9yg65

hola://ros-jurist[.]ru/9yg65

hola://sgph[.]comcastbiz[.]net/9yg65

hola://sherwoodbusiness[.]com/9yg65

hola://uwdesign[.]com[.]br/9yg65

hola://weijingart[.]com/9yg65

Ciphered Locky payload:

9yg65/tymbado2 – 4778ae5882e85897d481f1f278171e02

De-obfuscated Locky payload on disk:

redchip2.exe – ff19b6df5d38d754a7cbfb6acbb5157b

Locky command and control resources:

hola://188[.]120[.]239[.]230/checkupdate

hola://80[.]85[.]158[.]212/checkupdate

Locky ransom payment site:

g46mbrrzpfszonuk[.]onion

PhishMe Intelligence customers can find the full set of indicators and detailed reporting in Threat ID 8847 and Threat ID 8849.

Stay updated with the latest on Locky, Dridex, malware trends and more with our complimentary PhishMe Threat Alerts – delivered straight into your inbox.